13 Chapter Ten: Ethics of Professional Writing — Writing at Work: Introduction to Professional Writing

Chapter Ten: Ethics of Professional Writing

Applying Ethics in Technical and Professional Communication

Effective technical and professional communicators analyze and respond to context, genre conventions, deliverer-audience relationships, and other rhetorical elements. Understanding the variables and dynamics of specific rhetorical situations ensures that documents and presentations fulfill their purposes effectively, and that all parties are as satisfied as possible. However, rhetorical elements are not the only factors technical and professional communicators need to consider.

Beyond responding to their audiences and demonstrating mastery of genre conventions, technical and professional communicators must also make sure that they are communicating and behaving ethically. Broadly speaking, “ethics” refers to principles of right and wrong that govern your behavior and actions.

It is difficult to overstate the potential damage unethical professional communication can cause, including the theft of intellectual property, creating unsafe or toxic working conditions, upholding systems of oppression, and even causing environmental destruction. As daunting as it seems, this range of consequences also illustrates the power you have as a professional and the good you can do when you practice ethical communication and ensure that others do so as well.

As a professional, ethics applies to the way you conduct yourself on the job, the way you engage with colleagues, clients, subordinates, and superiors, and the way you utilize company time and resources. As a writer and speaker, ethics applies to how you present, arrange, and emphasize your ideas and those of others. Ethics also applies to the information you omit or suppress in a document, as well as how well you recognize and manage your biases when communicating and presenting ideas. This chapter will overview how important ethics are for a professional writer, what ethics means, as well as various situations for which you will have to think about the ethical implications.

Presentation of Information

How a writer presents information in a document can affect a reader’s understanding of the relative weight or seriousness of that information. On one hand, hiding a critical point in the middle of a long paragraph deep in a long document seriously deemphasizes that information. On the other hand, putting a minor point in a prominent spot (say, the first item in a bulleted list in a report’s executive summary) tells your reader that information is crucial.

Sometimes deemphasizing crucial information can lead to disastrous consequences. A classic example of this occurring is in the way NASA engineers wrote about the problem with O-ring seals in a memorandum report on the space shuttle Challenger, which exploded seconds after takeoff due to faulty engineering.[1] The crucial information about the O-rings was buried in a middle paragraph of the report, while information approving the launch was prominent in the beginning and ending. Presumably, the engineers were trying to present a full report, including identifying problematic components on the Challenger, but the memo’s audience of non-technical managers mistakenly believed the O-ring problem to be inconsequential, even if it was a real threat. The position of information in this document did not help them understand that the problem could be fatal.

Ethical writing thus involves not only being honest, but also presenting information so that your target audience will understand its relative importance and whether a technical fact is a good thing or a bad thing.

Typical Ethical Issues in Professional Writing

There are a few issues that may arise when a writer is researching a topic for the business or technical world.

Research that Does Not Support the Project Idea

In a technical document that contains research, you might discover conflicting data that does not support the project’s goal. For example, your small company has problems with employee morale. Research shows that bringing in an outside expert, someone who is unfamiliar with the company and the stakeholders, has the potential to enact the greatest change. You discover, however, that bringing in such an expert is cost-prohibitive. Should you leave this information out of your report on the matter, thereby encouraging your employer to pursue an action that is not really feasible? Conversely, should you include the information at the risk of not being able to offer the strongest solution?

Suppressing Relevant Information

Suppressing relevant information can involve a variety of factors, including the statistical significance of data or the researchers’ stake in the findings. For example, a study in 2015 found that driving while dehydrated is about as dangerous as driving while under the influence of alcohol. While this was widely reported in popular news sources, these sources failed to highlight some of the most important aspects of the study. To begin with, the study was conducted using just 12 people, and only 11 of them reported data. Furthermore, the study was conducted by an organization called the European Hydration Institute, which in turn is a think-tank subsidiary of the Coca-Cola corporation. In other words, not only was the sample size far too small to make a claim, but the data collection was designed and implemented by a corporation with a stake in the findings, since they profit off the sale of hydration products.[2] This case illustrates the ethical dubiousness of suppressing important contextual information for the sake of a sensational headline.

Not Verifying Sources Properly

Whenever you incorporate others’ ideas into your documents, especially quotations, make sure that you are attributing them to the correct source. Mark Twain, supposedly quoting British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, famously said, “There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics.”[3] On the other hand, H.G. Wells has been (mis)quoted as stating, “statistical thinking will one day be as necessary for efficient citizenship as the ability to read and write.”[4] When using quotes, even ones from famous figures that regularly appear as being commonly attributed to a particular person, it is important to verify the source of the quote. Such quotes often seem true, because the ideas they present are powerful and appealing. However, it is important to verify the original source both because you need to make sure both that your quote is, in fact, correct, and that it is not being taken out of context from the original source. Relatedly, the effective use of statistics can play a critical role in influencing public opinion, as well as in persuading in the workplace. However, as the first quotation indicates, statistics can be used to mislead rather than accurately inform—whether intentionally or unintentionally.

Presenting Visual Information Ethically

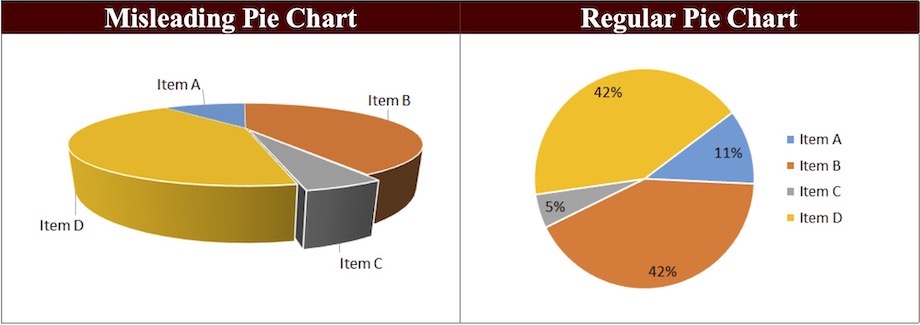

Visuals can be useful for efficiently communicating data and information for a reader. They provide data in a concentrated form, often illustrating key facts, statistics, or information from the text of a report. When writers present information visually, they have to be careful not to misrepresent or misreport the complete picture.

The image below shows information in a pie chart from two different perspectives. The data in each is identical, but the pie chart on the left presents the information in a misleading way. What do you notice about how that information is conveyed to the reader?

Imagine that these pie charts represented donations received by four candidates for city council. The candidate represented by the gray slice labeled “Item C” might think that she had received more donations than the candidate represented in the blue “Item A” slice. In fact, if we look at the same data in the 2D chart, we can see that Item C represents fewer than half of the donations compared to those for Item A. Thus, a simple change in perspective can change the impact of an image.

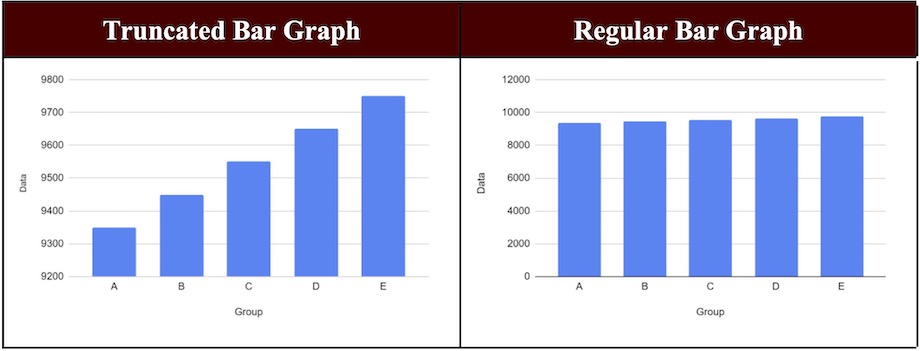

Similarly, take a look at the bar graphs in the image below. What do you notice about their presentation?

If the bar graph above were to represent sales figures for a company, the representation on the left would look like good news: dramatically increased sales over a five-year period. However, a closer look at the numbers reveals that the graph shows only a narrow range of numbers in a limited perspective (9100 to 9800). The bar graph on the right, on the other hand, shows the complete picture by presenting numbers from 0-1200 on the vertical axis, and we see that the sales figures have in fact been relatively stable for the past five years.

Presenting data in graphic form can be especially challenging. As you prepare your graphics, keep in mind the importance of providing appropriate context and perspective.

Limited Source Information in Research

Thorough research requires you to incorporate and synthesize information from a variety of reliable sources. Your document or presentation should demonstrate that you have examined your topic from as many angles as possible. Thus, your sources should include scholarly and professional research from a variety of appropriate databases and journals, as opposed to from just one author or website. Using a range of sources helps you avoid potential bias that can occur from relying on only a few experts. For example, if you were writing a report on the real estate market in Central Texas, then you would not collect data from only one broker’s office. While this office might have access to broader data on the real estate market, as a writer you run the risk of looking biased if you only choose materials from this one source. Collecting information from multiple brokers would demonstrate thorough and unbiased research. The next section of this chapter focuses on the ramifications of bias in more detail.

Information Inequity and Bias

Content warning: Because of the nature of inequity and bias, examples included in this section may be offensive or triggering for readers. Please be aware as you continue reading this portion of the text that instances of bias, harassment, and assault motivated by racial, ethnic, and gender biases are included to illustrate abstract concepts.

When evaluating the credibility of information, it is important to consider its bias. Bias, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, is “An inclination, leaning, tendency, bent; a preponderating disposition or propensity; predisposition towards; predilection; prejudice.”[5] Bias does not always immediately indicate an overt prejudice or a political leaning. However, in many cases, bias can be prejudicial and harmful. For example, in 2018, Eugene Scott analyzed the use of “dog whistling” in American politics for The Washington Post. Dog whistling is the use of coded language or images to appeal to voters’ unconscious biases. Scott references multiple examples of dog whistling in his article, such as Florida Governor Ron DeSantis cautioning voters that if his then-opponent Andrew Gillum (a Black man) were elected, he would “monkey this up.” While DeSantis disavowed any explicit racist intent behind his words, they are contextually rooted in a long-standing racial stereotype against Black people, regardless of intent.

You may also remember in 2017 when Pepsi partnered with Kendall Jenner to appropriate the Black Lives Matter movement in an advertisement to sell soda.[6] Audiences quickly responded, and Pepsi pulled the insensitive ad. Editor of HuffPost Black Voices Taryn Finley, for one, called out Pepsi for its oversimplification of serious issues, calling the ad “tone-deaf, shallow, and over-produced.”[7] Her tweet implicitly points out the way that reducing the troubles and consequences of “-isms” to something that can be so easily solved trivializes the experiences of those who have struggled with those systemic “-isms,” especially those who have been negatively affected by racism in its various forms. Ultimately, Pepsi’s ad and Finley’s response to it both highlight the consequences of failing to account for bias in professional communication.

Implicit and Explicit Bias

First, it is important to acknowledge that all information is biased in some way. There are two primary types of bias: explicit and implicit. The Office of Diversity and Outreach at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) offers an easy way to distinguish between the two:

Explicit bias is a conscious bias, meaning that we are aware of it. In contrast, implicit bias is an unconscious bias, meaning that we don’t even realize we hold it.[8] Implicit bias starts during early childhood, so that by the time we are in adolescence, we already hold prejudices against certain groups, even if this runs against our conscious morals or ethics.[9] The good news, though, is that our implicit biases can change and are often more a product of our environment than anything else.[10]

Implicit and explicit biases become problems because of the way our brains work. Psychologists say that we either process information quickly based on our prior knowledge, or are very deliberative and think critically about information.[11] We rely upon our biases when we make quick decisions, but we can override such preconditions when we think deliberately and critically. According to cognitive psychologist Daniel T. Willingham, there really isn’t a clear cut way to “teach” ourselves how to become better critical thinkers, but it is possible, and anyone can do it.[12] Willingham has found that learning deeply about a subject, drawing from and challenging our life experiences, and developing critical thinking strategies to follow when evaluating information all help us avoid cognitive biases.

Cognitive bias is a systemically pervasive error in our assessment of people, issues, situations, and environments, which ultimately shapes the way we act or form judgements.[13] Many biases stem from cognitive bias, and these biases have lasting effects on how we choose to consume information and news.

Categories of Bias

The following sections cover the most common forms of bias. Each section details how each form of bias functions, highlights whom it affects, and provides concrete examples. As you review these categories, take a moment to reflect on times you have encountered these forms of bias or even may have exhibited them. Everyone has unconsciously practiced at least one form of bias or another at some point, and bias in thinking inevitably leads to bias in writing and speaking. In short, being familiar with these categories of bias is important in becoming a more effective, ethical, and socially just communicator.

Filter Bubbles

Filter bubbles refer to our tendency to consume news and other information that support our preconceived notions, and to reject information that challenges these notions. Three categories of cognitive bias seem to sustain these filter bubbles:

The Hostile Media Effect is “a perceptual bias in which…people highly involved with an issue or interest group…tend to see media coverage of that issue or group as unfairly slanted against their own position.”[14]

The Dunning-Kruger Effect is the tendency of those with low ability in or knowledge of a topic to overestimate their competency in that topic, and/or underestimate the complexity of that topic.[15]

Confirmation bias occurs when we only seek out and trust sources of information that confirm our own opinions.[16] Have you ever chosen a topic for a research paper and sought out sources that only confirmed your thesis on that topic? That is an example of confirmation bias. Biases shape the filter bubbles in which we consume information and, as you will read below, play into cultural biases as well.

Gender Bias

Gender bias occurs when a writer privileges the words and experiences of people of a particular gender over those of others. In professional writing, gender bias can often be seen in the use of pronouns (always using “he” as opposed to the singular “they,” “he or she,”[17] or interchanging pronoun use throughout a document). Other common manifestations of gender bias include: citing primarily men or individuals with male-sounding names to the exclusion of women, nonbinary, or gender-fluid individuals; citing only a male scholar even though a female scholar published similar conclusions earlier; and using different standards for praising men and women.

Especially in performance reviews and letters of recommendation, women are more likely to be praised (and criticized) for how they are perceived socially, with words such as “caring,” “compassionate,” and “nurturing.” Men, in contrast, are typically praised in terms associated with their intelligence and competence, such as “brilliant” and “skilled.”[18] In one study conducted by Hoffman, et al., some letters of recommendation for female applicants applying for a pediatric surgery fellowship “mentioned [their] spouse’s accomplishments,” whereas letters supporting male applicants did not include spousal accomplishments.[19] Due to gender bias, certain words such as “assertive,” which are seen as positive for men (where “assertive” implies strength and good leadership) can be coded as negative for women and queer individuals (where “assertive” implies that they are opinionated and loud).

You can also see gender biases reflected in the media. In November 2017, NBC News anchor Savannah Guthrie announced live on the Today Show that her co-host, Matt Lauer, had been terminated due to revelations of sexual misconduct.[20] While he was officially terminated as the result of one specific incident involving an anonymous NBC News colleague, there was reason to believe that this was not an isolated incident, but rather part of an ongoing cycle of systemic sexual harassment involving Lauer at NBC News.[21] In light of his termination, USA Today published a video compilation of moments in which Lauer exhibited sexist or crude behavior during interviews of prominent celebrities and politicians, including a moderated discussion between Hillary Clinton and then-presidential candidate Donald Trump.[22] While Lauer grilled Clinton on her use of a private email server, he breezed through his conversation with Trump. It can be argued that, based on the totality of these instances, Lauer exhibited gender bias.

Racial Bias

The Annie E. Casey Foundation, a racial justice organization, frames racism as an umbrella term composed of a set of nuanced, context-specific forms of racism.

Racism is widely thought of as simply personal prejudice, but, in fact, it is a complex system of racial hierarchies and inequities. At the micro, or individual, level of racism are internalized and interpersonal racisms. At the macro level of racism, we look beyond the individual to broader dynamics, including institutional and structural racism.

Internalized racism describes the private racial beliefs held by and within individuals.

Interpersonal racism is how our private beliefs about race become public when we interact with others.

Institutional racism is racial inequity within institutions and systems of power, such as places of employment, government agencies, and in social services.

Structural racism (or structural racialization) is the racial bias across institutions and society. It describes the cumulative and compounding effects of an array of factors that systematically privilege white people and disadvantage people of color.[23]

In other words, a complex and context-specific definition of racism is essential, because racism can take many forms and may be encountered through a number of overt racial macroaggressions and more subtle microaggressions.[24]

Such racial aggressions are able to occur because of white privilege. White privilege is “an invisible package of unearned assets which I can count on cashing in each day,” as Women’s Studies scholar Peggy McIntosh[25] defines it in “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack.”[26] In this essay, McIntosh delineates how whites are “carefully taught” not to recognize how they benefit daily from various forms of racism and the racial hierarchy. Her examples include how whites are able to socialize with people in their own racial group and disassociate from people they’ve learned to mistrust. In other words, white people can choose to only associate with white people and get by just fine, whereas a group of non-white people selectively associating might raise suspicions.

In technical and professional documents, racial bias often occurs by omission. A presentation, for example, that only uses white and white-passing models in photographs, or highlights white models in positions of power while showing Black and Brown models only in subservient or non-executive roles, visually reinforces structures of white supremacy. In research reports, writers who gloss over key contributions of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color) researchers while focusing solely on those of white researchers also exhibit racial bias.

In other types of writing, a writer may exhibit racial bias in how they describe individuals of different races. For example, one could see this in the media when it covers two domestic shooting cases. In one case, the white assailant, who had a history of domestic violence, might be described sympathetically, with media reports remarking on his mental illness and good-natured public personality. The Black assailant, however, might not receive such treatment. Media instead may focus on his past domestic violence and drug charges.

Ethnicity and Ethnic Prejudice

Ethnicity is a term that describes shared culture—the practices, values, and beliefs of a group. This might include shared language, religion, and traditions, among other commonalities. Like race, the term “ethnicity” is difficult to describe, and its meaning has changed over time. And also like with their race, individuals may be identified or self-identify with ethnicities in complex, even contradictory, ways. For example, ethnic groups such as Irish, Italian, Russian, Jewish, and Serbian Americans might all be groups whose members are predominantly included in the racial category “white.” Conversely, the ethnic group “British” includes citizens from a multiplicity of racial backgrounds: Black, white, Asian, and more, plus a variety of racial combinations. These examples illustrate the complexity and overlap of these identifying terms. Ethnicity, like race, continues to be an identification method that individuals and institutions use today—whether through the census, affirmative action initiatives, non-discrimination laws, or simply in personal day-to-day relations.

Ethnic prejudice and racial prejudice are often conflated. Like racism, ethnic prejudice also occurs through acts of micro- and macroaggressions. Ethnic prejudice, however, focuses primarily on a group’s shared culture rather than on a group’s race, even as race may also be part of that culture’s identity. The word “bigotry” is also often conflated with “racism”; however, “bigotry” refers primarily to ethnic prejudice, even though race may also be a part of a group’s identity.

Particularly in the field of journalism, ethnic biases have come to the forefront when the media reports on Latinx communities and on the topic of immigration. For example, Cecilia Menjívar, professor of sociology at UCLA, has found that negative media portrayals of Latinx immigrants often reinforce negative stereotypes of Latinx people, which leaves Latinx people striving to debunk such misperceptions in their daily lives.[27] Joseph Erba, assistant professor of journalism at the University of Kansas, likewise found that such stereotypes threatened the experience of Latinx college students, forcing them to combat the negative perceptions of them held by their non-Latinx classmates throughout their time on campus.[28]

Corporate Bias

Corporate bias occurs when a news agency, media conglomerate, or accreditation agency privileges the interests of its ownership or financial backers, such as an employer, client, or advertiser.

In advertising and strategic communications, corporate bias is part of the nature of the work. Your clients essentially pay you to represent them in a positive light. However, you have to walk an ethical line when doing so. Advertisers must remain mindful of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which enforces truth-in-advertising laws.[29] Public Relations practitioners must be guided by the Public Relations Society of America’s code of ethics.[30]

In your role as a communicator, you act as a type of intermediary between the public and your client. Even though your client may pay you to promote them or their product, you must do so with the best interest of the public in mind. For instance, if you represent a celebrity who is paid to make Instagram posts of themselves with products, then you will have to remind them to clearly state that these are paid advertisements and not just cute photos, in order to adhere to the FTC’s advertising regulations.[31]

Or if, for example, you are developing a health-themed ad campaign for Rice Krispies cereal claiming that the cereal will boost a child’s immunity, then you should make certain that scientists have verified that claim. When the FTC fined Kellogg’s for not backing up this claim with scientific evidence, the cereal company had to pull all advertising that sported the claim.[32]

Algorithms: Human-Inspired Bias

Loosely defined, algorithms are sets of rules that computers use to perform a specific task. Based in mathematics and computer science, algorithms are usually numbers-based and in code form. Using an algorithm, a machine can quickly and autonomously calculate a result. Social media companies including Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube use algorithms to determine what posts appear at the top of your scrolling feed or what videos to recommend.

However, while algorithms use numbers, they are not immune to bias, whether on the part of the searcher or the creator. In her book Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism, Safiya Umoja Noble details the biases inherent in Google searches. Much of her research stems from a 2010 incident in which the top results of a Google search of “black girls” yielded explicit pornographic content. Noble argues that these primary representations of Black women in Google searches are representative of a “corporate logic of either willful neglect or a profit imperative that makes money from racism and sexism.”[33]

What this all means for researchers is that you have to be particularly careful when searching for reliable sources, especially if you’re using a popular search engine like Google. Your prior search history, the search history of other users, and the impact of paid advertisers will influence which hits you see first, if at all. Using your university’s library service will help mitigate this issue, but be aware that there are racial, gender, and ethnic biases in all coding. Consulting references made in peer-reviewed journal articles is another helpful option to mitigate the issue, though these reference lists may also inadvertently miss key voices. When searching, therefore, you will need to actively look for perspectives that privilege marginalized voices. This research will require you to read widely and understand both the accepted conventions and controversies in your field.

Some Ways Forward

There is no simple fix for these deeply problematic and complicated issues. However, there are options for conscious writers when addressing their own bias or the bias in their chosen field. As a writer, you need to be aware of biases and actively work to combat them.

Work Toward Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI)

An increasingly important part of workplace culture is to seek to make people from various backgrounds feel welcome, safe, and supported to do their role to their fullest capabilities. Diversity is the presence of differences in a given setting. Equity ensures that every person has received fair, impartial, and equal opportunities. Inclusion provides a sense of belonging and support from one’s organization. Together, these principles provide a strong company ethic, shaped by an awareness of the diverse voices and values employees bring to the company.

There is a lot a professional writer can do to learn more about how they can promote DEI. This is extremely important because you will learn how equitable employers are able to outpace their competitors by including unique perspectives. Whether you are working on DEI materials to help others in the workplace or are working to educate yourself on DEI by looking at your own implicit bias, understanding the role a professional writer can have in DEI initiatives is critical.

Diversify Your Sources

Journalists Ed Yong and Adrienne La France worked to fix the unintentional gender bias they discovered in their own work by pledging to be more intentional about including women among their sources. Yong, for example, now spends more time searching for sources until he has a list of female contacts. Additionally, he tracks who he contacts and interviews for stories. As a result of his mindfulness, Yong now cites women about 50 percent of the time. This also has catalyzed him to start tracking how many times he includes voices of people of color, LGBTQ folks, immigrants, and individuals with disabilities.[34] LaFrance, meanwhile, revised her list of go-to sources and seeks out stories that focus on the achievements of women.[35]

In research, “diversifying your sources” also entails revising research methods and project design. When designing a research project that requires human subjects, be sure to directly include subjects of all cultures and genders. Considerable medical and social research relies on a sample size of predominantly white men, and while these results are valuable, the findings are often not immediately applicable to women, people of color, or individuals of lower socioeconomic status.

Write Inclusively

Once you have identified a diverse pool of sources, it is important to conduct inclusive reporting. Writing about the developing journalism ethics of covering transgender people, reporter Christine Grimaldi outlines some important tips.[36] She suggests asking people their pronouns (she, him, they, xe, or ze), and then using such pronouns in your work. Other examples of inclusive writing include paying attention to how you describe individuals. Do you equally emphasize the accomplishments of men, women, trans, and nonbinary people? When you are referring to individuals or communities with disabilities, are you familiar with the terms they use to self-identify, and do you show respect by adhering to their conventions? Is the term you are using to describe one person the same you would use to describe another of a different race, sexuality, gender, or ability, given the same information? Further still, do you recognize that language constantly evolves, and that you should update your use of identifying terminology to reflect this evolution?

Recognize that there are many experts and professional organizations you can turn to for guidance. For instance, the National Association of Black Journalists has its own style guide,[37] and the National Association of Hispanic Journalists offers points of guidance.[38] These are just a few examples.

Contribute to a Positive Workplace Culture

A workplace culture is the values, belief systems, and attitudes shared by people in a shared workplace. In a workplace, the culture is often shaped by the leadership and management. The culture of workplaces set forth the ethos and values of an organization. A positive workplace culture has been shown to foster an inclusive work environment, better communication and collaboration,[39] and employee engagement and satisfaction.[40]

With a growing focus on areas such as flexible hours, mental health support, and taking action based on employee feedback, workplace culture is now more important than ever. When employees truly feel that their company is a great place to work, they feel happier and more fulfilled in their jobs.

Acting Ethically & Responding to Unethical Situations

While communication plays a significant role in technical and professional ethics, it is also important to understand what it entails to be ethical and act ethically. Most people do not require a textbook to understand that embezzlement and nepotism are unethical. At the same time, these situations do occur, and you may not know how to respond to them in the moment—especially if you do not have prior experience with them.

To promote effective and ethical responses to unethical situations, most organizations and employers provide recurring job training on some of the more common scenarios when egregious unethical behavior can occur. These scenarios include:

Whistleblowing. Whistleblowing occurs when a member of an organization (usually someone of lower rank) reports unethical activity that is pervasive (usually committed by someone of higher rank). This can include fraudulent business practices, sexual harassment, corporate espionage, etc. Unfortunately, whistleblowers are often punished for exposing unethical activity. Should you be in a situation when you are obligated to report unethical activity, make sure you are aware of the protections and resources at your disposal, as well as potential consequences. Conversely, if you are in a position to protect a whistleblower’s privacy and safety (e.g., if you are a journalist), you are obligated to do so.

Respecting and Promoting Diversity. Understand that diversity issues affect populations in two main ways: treatment and impact. We usually know not to institute policies that deliberately single out a group or individual, such as having a workplace dress code for women but not for men. Do not, however, commit the fallacy of “treating everyone exactly the same.” While doing so may seem on its surface like a fail-safe for promoting diversity, different communities will experience different impacts from that seemingly equal treatment. For example, requiring all employees to have a valid driver’s license, even for those jobs that do not require driving for work, would be discriminatory in that it would exclude people with disabilities who are unable to drive, but who do have other adequate means to arrive at work on time.

If your organization has a space for members or employees in marginalized communities (such as a campus diversity office), respect their privacy and do not attempt to insert yourself in that space. Make sure that you properly acknowledge and uplift the work of all employees, and empower them if you are in a position to do so. Creating a work environment that values diversity goes far beyond the hiring process. Always defer to the perspectives of communities you are not a member of on issues that concern those communities. Whenever possible, make sure that decisions that could affect a particular community are made by members of that community.

Ethics of diversity in technical communication go beyond interpersonal communication in the workplace. The documents that we produce as working professionals should also promote diversity in their language and appearance. For example, when creating a brochure that includes pictures of people, make sure that multiple races, genders, and ages are represented in those images.

Careful language choices can also help you be an ethical technical communicator in matters of diversity. For example, it is now customary to capitalize the words “Black” and “Brown” when writing about Black and Brown people. When writing about people with disabilities, it is usually good form to foreground personhood instead of the disability. For instance, instead of writing about “wheelchair-bound people,” write about “people who use wheelchairs.” In the latter, more ethical example, a wheelchair is a tool that people who have mobility impairments can choose to use to improve their mobility. However, members of some communities, such as deaf people and blind people, may prefer to be described as such.

Likewise, be sensitive to pronoun usage. Correct grammatical practice today involves using the pronoun “they” as a singular form in place of older constructs such as “he or she” or “s/he.” For an individual’s pronoun, consult the individual. When writing examples and scenarios that call for you to use names, be sure to use names representing a variety of genders, cultures, and communities.

Sexual Harassment. Respect the personal space and privacy of other members in your organization, and never use institutional power to take advantage of a subordinate. If someone in your organization discloses that they were the victim of sexual harassment, encourage them to report it to Human Resources and respect the victim’s right to report. However, also keep in mind that laws such as Title IX require organizations like universities to report sexual harassment, whether or not the victim wants this outcome. In those situations, be sure to inform the victim of your obligation to report in advance.

Theft or Abuse of Company Resources. Theft from an organization can manifest in a variety of forms. While we often think of theft in terms of money, such as embezzlement or tax fraud, it can also apply to company property, such as office supplies. Additionally, it is becoming increasingly common for workers to boost their income through freelance work or a second, part-time, job—i.e., a side-hustle. While there is nothing wrong with doing so, be sure to keep this separate from your main job. For example, do not run your YouTube channel using your company computer or A/V equipment. If your second job creates a conflict of interest with your primary employer (such as freelancing for a competitor), you must report that activity.

In all situations where unethical activity could potentially occur, always be mindful of your words and actions. You are responsible for ensuring that you are not enabling or contributing to this activity, even inadvertently. Consider the consequences, short- and long-term, for all people involved in these situations, and be aware of the resources and procedures in place for reporting unethical activity. With luck, you will never have to apply this knowledge, but it is far better to possess it and not need it than the reverse.

Additional Resources

“NAIWE Code of Ethics,” National Association of Independent Writers and Editors.

“Integrated DEI for Written Materials: Make Your Written Words Mean More,” Dr. Breeze H.

“Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Technical Communication,” Wendy Ross, STC Rochester.

Hiring a Chief Diversity Officer Won’t Fix Your Racist Company Culture,” Nadia Owusu.

“15 Key Benefits of DEI to Communicate With Team Members,” Forbes Human Resources Council.

“Employee Experience is as Strong as Ever at the 100 Best Companies,” Michael Bush and Great Place to Work.

“Why 2022 is the Year of Workplace Culture,” Caroline Castrillion.

This chapter is derived from:

Hamlin, Annemarie, Chris Rubio, and Michele DeSilva, “Presentation of Information,” licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. In Allison Gross, Annemarie Hamlin, Billy Merck, Chris Rubio, Jodi Naas, Megan Savage, and Michele DeSilva. Technical Writing. Open Oregon Educational Materials, n.d. https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/technicalwriting/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Last, Suzan, with contributors Candice Neveu and Monika Smith. Technical Writing Essentials: Introduction to Professional Communications in Technical Fields. Victoria, BC: University of Victoria, 2019. https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/technicalwriting/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Little, William, with contributors Sally Vyain, Gail Scaramuzzo, Susan Cody-Rydzewski, Heather Griffiths, Eric Strayer, Nathan Keirns, and Ron McGivern. Introduction to Sociology, 1st Canadian Edition. Victoria, BC: BCcampus, 2014. https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

McKinney, Matt, Kalani Pattison, Sarah LeMire, Kathy Anders, Gia Alexander, and Nicole Hagstrom-Schmidt, eds. Howdy or Hello?: Technical and Professional Communication. 2nd ed. College Station: Texas A&M University, 2022. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Younger, Karna, and Callie Branstiter. “Contend With Bias.” In Be Credible: Information Literacy for Journalism, Public Relations, Advertising and Marketing Students by Peter Bobkowski and Karna Younger. Lawrence, KS: Peter Bobkowski and Karna Younger, 2018. https://dx.doi.org/10.17161/1808.27350. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

- Presidential Commission on the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident, “Chapter VI: An Accident Routed in History,” in Report to the President (Washington, DC, June 6, 1986). Available at NASA History, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, https://history.nasa.gov/rogersrep/v1ch6.htm. ↵

- Ryan Reed, “Watch John Oliver Call Out Bogus Scientific Studies.” Rolling Stone, May 9, 2016. https://www.rollingstone.com/tv/tv-news/watch-john-oliver-call-out-bogus-scientific-studies-60448/; John Oliver, “Scientific Studies: Last Week Tonight with John Oliver (HBO).” LastWeekTonight, YouTube, May 8, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Rnq1NpHdmw. ↵

- Mark Twain, Mark Twain’s Autobiography, Volume 1 (Project Gutenberg of Australia, 2002), Project Gutenberg Australia, https://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks02/0200551h.html. ↵

- This particular quote comes from Samuel S. Wilkes, who is misquoting H.G. Wells. S.S. Wilkes, “Undergraduate Statistical Education,” Journal of the American Statistical Association, 46, no. 253 (March 1951): 5, https://doi.org/ 10.1080/01621459.1951.10500763. ↵

- “Bias, n. B.3.a.,” OED Online, accessed June 2020, https://www.oed.com/. ↵

- Kristina Monllos, “Pepsi’s Tone-Deaf Kendall Jenner Ad Co-opting the Resistance Is Getting Clobbered in Social,” Adweek, April 4, 2017, http://www.adweek.com/brand-marketing/pepsis-tone-deaf-kendall-jenner-ad-co-opting-the-resistance-is-getting-clobbered-in-social/. ↵

- Taryn Finley, “Kendall Jenner gives a Pepsi to a cop and rids the world of -isms. Y’all can go somewhere with this tone-deaf, shallow and over-produced ad,” @_TARYNitUP, Twitter, April 4, 2017, https://twitter.com/_TARYNitUP/status/849378436577669121?s=20. ↵

- Renee Navarro, “What is Unconscious Bias?,” University of California, San Francisco: Office of Diversity and Outreach, accessed August 10, 2020, https://diversity.ucsf.edu/resources/unconscious-bias. ↵

- Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity, “Understanding Implicit Bias,” The Ohio State University, accessed August 11, 2020, https://web.archive.org/web/20180912211808/http://kirwaninstitute.osu.edu/research/understanding-implicit-bias/. ↵

- Nilanjana Dasgupta, “Chapter Five – Implicit Attitudes and Beliefs Adapt to Situations: A Decade of Research on the Malleability of Implicit Prejudice, Stereotypes, and the Self-Concept,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, vol. 47, ed. Mark P. Zanna, Patricia Devine, James M. Olson, and Ashby Plant (San Diego, CA: Academic Press, 2013): 233-279, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-407236-7.00005-X.x ↵

- Patrick McNamara, “Dual Process Theories of Mind and Dreams,” Psychology Today, March 11, 2013, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/dream-catcher/201303/dual-process-theories-mind-and-dreams. ↵

- Daniel T. Willingham, “Critical Thinking: Why Is It So Hard to Teach?,” American Educator (Summer 2007): 10, https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/periodicals/Crit_Thinking.pdf. ↵

- Kendra Cherry, “What is Cognitive Bias?” Verywell Mind. Reviewed by Amy Morin, LCSW, on July 19, 2020. Accessed January 12, 2021. https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-a-cognitive-bias-2794963. ↵

- Albert C. Gunther, “Hostile Media Phenomenon,” in The International Encyclopedia of Communication, ed. W. Donsbach. Wiley Online Library, July 9, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405186407.wbiech023.pub2. ↵

- Brian Duignan, “Dunning-Kruger Effect,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, July 26, 2019, https://www.britannica.com/science/Dunning-Kruger-effect. ↵

- Bettina J. Casad, “Confirmation Bias,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, October 9, 2019, https://www.britannica.com/science/confirmation-bias. ↵

- “He or she” is a traditional corrective strategy for the exclusive use of “he,” but this is becoming dated, as it excludes nonbinary and gender-fluid people. ↵

- Gender bias exists across evaluations in most, if not every, professional field. See: Karen S. Lyness and Madeline E. Heilman, “When Fit is Fundamental: Performance Evaluations and Promotions of Upper-Level Female and Male Managers,” Journal of Applied Psychology 91, no. 4 (2006): 777–785. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.4.777; David G. Smith, Judith E. Rosenstein, Margaret C. Nikolov, and Darby A. Chaney, “The Power of Language: Gender, Status, and Agency in Performance Evaluations,” Sex Roles 80, no. 3/4 (February 2019): 159–171. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11199-018-0923-7; and David A. Ross, Dowin Boatright, Marcella Nunez-Smith, Ayana Jordan, Adam Chekroud, and Edward Z. Moore, “Differences in Words Used to Describe Racial and Gender Groups in Medical Student Performance Evaluations,” PLoS ONE 12, no. 8 (August 9, 2017): 1–10. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0181659. ↵

- Aria Hoffman, Rachel Ghoubrial, Melanie McCormick, Praise Maternavi, and Robert Cusick, “Exploring the Gender Gap: Letters of Recommendation to Pediatric Surgery Fellowship,” The American Journal of Surgery 219, no. 6 (June 2020): 932-936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2019.08.005. ↵

- “Matt Lauer Has Been Terminated from NBC News,” Today, NBC Universal, November 29, 2017, https://www.today.com/video/matt-lauer-has-been-terminated-from-nbc-news-1105840707690. ↵

- Yohana Desta, “Graphic, Disturbing Details of Matt Lauer’s Alleged Sexual Misconduct,” Vanity Fair: Hollywood, November 29, 2017, https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2017/11/matt-lauer-sexual-misconduct-allegations. ↵

- Carly Mallenbaum, “Awkward Matt Lauer TV Moments Resurface in Wake of Firing,” USA Today, November 29, 2017, https://www.usatoday.com/story/life/people/2017/11/29/matt-lauer-fired-hathaway-awkward/906536001/. ↵

- The Annie E. Casey Foundation, “Equity vs. Equality and Other Racial Justice Definitions.” Annie E. Casey Foundation Blog, accessed August 24, 2020, aecf.org/blog/racial-justice-definitions/. ↵

- “Examples of Racial Microaggressions,” University of Minnesota School of Public Health, accessed August 11, 2020, https://sph.umn.edu/site/docs/hewg/microaggressions.pdf. Document indicates that it was adapted from: Derald Wing Sue, et al., “Racial Microaggressions in Everyday Life: Implications for Clinical Practice,” American Psychologist 62, no. 4 (2007): 271-286, https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2007-07130-001?doi=1. ↵

- “Peggy McIntosh,” Wikipedia, accessed August 11, 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peggy_McIntosh. ↵

- Peggy McIntosh, “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack,” Peace and Freedom Magazine, (July/August 1989): 10-12, https://www.wcwonline.org/images/pdf/Knapsack_plus_Notes-Peggy_McIntosh.pdf. ↵

- George Diepenbrock, “Negative Media Portrayals Drive Perception of Immigration Policy, Study Finds,” KU Today, December 6, 2016, https://news.ku.edu/2016/11/29/negative-media-portrayals-drive-perception-immigrants-study-finds. ↵

- Mike Krings, “Study Shows Media Stereotypes Shape How Latinos Experience College,” KU Today, September 8, 2015, https://news.ku.edu/2015/08/28/study-shows-media-stereotypes-shape-how-latino-college-students-experience-college. ↵

- “Truth in Advertising,” Federal Trade Commission, accessed August 11, 2020, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/media-resources/truth-advertising. ↵

- “PRSA Code of Ethics,” Public Relations Society of America, Inc., accessed August 11, 2020, https://www.prsa.org/about/ethics/prsa-code-of-ethics. ↵

- Federal Trade Commission, “FTC Staff Reminds Influencers and Brands to Clearly Disclose Relationship,” Federal Trade Commission: Press Releases, April 19, 2017, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2017/04/ftc-staff-reminds-influencers-brands-clearly-disclose. ↵

- Saundra Young, “Kellogg Settles Risk Krispies False Ad Case,” CNN: The Chart Blog (June 4, 2010), accessed August 11, 2020, https://thechart.blogs.cnn.com/2010/06/04/kellogg-settles-rice-krispies-false-ad-case/. ↵

- Safiya Umoja Noble, Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism (New York: New York University Press, 2018), 5. ↵

- Ed Yong, “I Spent Two Years Trying to Fix the Gender Imbalance in My Stories: Here’s What I’ve Learned, and Why I Did It,” The Atlantic: Science, February 6, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2018/02/i-spent-two-years-trying-to-fix-the-gender-imbalance-in-my-stories/552404/. ↵

- Adrienne La France, “ I Analyzed a Year of My Reporting for Gender Bias (Again),” The Atlantic: Technology, February 17, 2016, https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2016/02/gender-diversity-journalism/463023/. ↵

- Christine Grimaldi, “I Tripped Up While Reporting on Gender and Sexuality. Here’s What I Learned,” Columbia Journalism Review, September 1, 2016, https://www.cjr.org/the_feature/gender_sexuality_reporting.php. ↵

- National Association of Black Journalists, NABJ Style Guide, accessed August 11, 2020, https://www.nabj.org/page/styleguide. ↵

- National Association of Hispanic Journalists, Cultural Competence Handbook (Washington, DC: NAHJ, 2020), https://nahj.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/NAHJ-Cultural-Compliance-Handbook-Revised-8-3-20-FINAL.pdf. ↵

- Pragya Agarwal, “How to Create a Positive Workplace Culture,” Forbes, August 29, 2018, https://www.forbes.com/sites/pragyaagarwaleurope/2018/08/29/how-to-create-a-positive-work-place-culture/?sh=74f6cd2d4272. ↵

- “Workplace Culture: What it is and Why it Matters,” Employers Resource Council, February 1, 2019, https://yourerc.com/blog/post/workplace-culture-what-it-is-why-it-matters-how-to-define-it. ↵