8 History of Wildlife in North America

The following is a brief history of human-wildlife interactions in North America. The rather arbitrary “eras” used in this historical account follow Shaw (1985). Colonization of North America by Europeans began in the early 1600s when Europe was largely in a late agrarian stage of cultural development. The United States was founded during the early transition from a late agrarian to an early industrial economy. Much of the continent, especially the western regions, was settled during this transitional time period. In contrast, Native Americans were living in hunter-gatherer or horticultural societies at the time of European colonization and American expansion. The clashes between these two cultures had tragic consequences for the Native Americans and also resulted in dramatic declines in wildlife. The 20th century roughly corresponds with the transition of North America to a late industrial economy. Not surprisingly, a dramatic shift in the attitudes toward nature and the development of the conservation movement occurred during that time. This chapter documents these changes.

Pre-European Era (11,500 B.C. to 1500 AD)

Humans invaded North America some time during the last ice age, roughly 13,500 years ago, when sea levels were lower and it was presumably possible to walk across the Bering Land Bridge connecting Siberia and Alaska (Flannery 2001). Although evidence is scanty, it seems likely that once the glaciers melted sufficiently to allow their passage out of Alaska, the colonizing humans spread across the continent and throughout South America in less than 1000 years. From the beginning, these people probably had a major impact on wildlife.

Before humans entered the picture, North America had an impressive assortment of large mammals and birds. The herbivores of this megafauna included 3 species of elephants (woolly mammoths, giant mammoths, and mastodons), horses, camels, giant bison, giant ground sloths, giant armadillos, tapirs, giant beaver, giant tortoises (roughly the size of Volkswagon bugs), and a peccary as large as the wild boars of Europe. An entire guild of now extinct mega-predators existed to feed on these large herbivores, including cheetahs, saber-toothed tigers, giant wolves, and two species of lion (one larger than the modern lions of Africa). There also existed a truly fearsome short-nosed bear, about twice the size of a modern grizzly bear, which ran its prey down like modern wolves do. Jaguars lived far north of their current tropical latitudes, into the boreal forests of Canada, as did many of the New World cats now restricted to Central and South America. There also existed a guild of large meat-eating birds, the largest of which were the teratorns, scavengers with wingspans up to five meters. The endangered California condor is the last remnant of these giant scavenger birds. There was even a giant vampire bat adapted to feeding off the blood of these enormous beasts.

The fate of all these species has been the topic of much scientific debate, but the majority of the evidence supports the hypothesis of “Pleistocene Overkill” (Martin and Wright 1967, Flannery 2001). This hypothesis suggests that as humans spread across the two continents, they preyed upon the large herbivores, such as mammoths, ground sloths, and horses, and wiped them out. Such large animals are more vulnerable to extinction than smaller ones because they cannot hide as easily, and because their lower reproductive rates cannot compensate for the losses due to hunting. They also may have had a fearlessness of humans, somewhat like the dodo bird, because these animals evolved with out human presence. When the large herbivores disappeared, their natural predators, such as saber-toothed tigers and short-nosed bears, became extinct as well. The large scavenger bird species, adapted to eating the remains of large animals, then followed into extinction. The California condor may have held on because it had access to the carcasses of marine mammals, which did not suffer high extinction rates at this time. The loss of the megafauna also impacted the diversity of smaller animals. Because large abundant animals (such as mammoths) alter plant communities by their intense grazing practices, their disappearance caused a major shift in the plant communities (e.g., from prairie to forest) resulting in the extinction of many smaller species that depended on the habitats maintained by the large grazers. In fact, there existed a grassland ecosystem in Alaska called the mammoth steppe that disappeared entirely once the woolly mammoth went extinct in that region, which is attributed the change in ecosystem processes that occurred when this keystone herbivore was lost (Flannery 2001).

The scenario of Pleistocene Overkill has been controversial. The principal alternative hypothesis to explain the rapid loss of this megafauna is the impact of climatic changes that occurred with the end of the ice age 13,000 years ago. There has also been a tendency to challenge the Pleistocene Overkill hypothesis by those who want to romanticize hunter-gatherers as living perfectly in balance with nature. But new data and discoveries by scientists increasingly confirm that the first Native Americans were indeed responsible for the extinction of these species. Evidence includes the finding of remains of mammoths and giant sloths butchered by humans and the general occurrence of widespread extinction coincident with the spread of humans. The Clovis people were the first humans to colonize North America. Their distinctive, beautifully made stone spearheads were well adapted to killing large herbivores and have been found by archaeologists imbedded in the skeletons of large prey at many kill sites. This Clovis culture rapidly spread throughout North America, and then rather abruptly disappeared after about 300 years. The disappearance of the Clovis spearheads coincided almost exactly with extinction of the large game of North America. The physical conditions of mammoths at the time of the Clovis culture just before their extinction can be determined by looking at the growth rings in their tusks, which indicate that the animals were getting plenty of nutrition, reproducing frequently, and not experiencing the starvation stress that would accompany climate-driven extinction. In addition, many of the extinct species of megafauna had already survived several other glacial/interglacial climate cycles, and so presumably they could have survived one more. Furthermore, very similar patterns of extinction of megafauna occurred in Australia when humans first colonized that continent (Flannery 1994); this extinction event, however, did not coincide with a period of climate change. Overall it is estimated that the Pleistocene Overkill hypothesis illustrates a widely accepted fact: even hunter-gatherer humans were capable of having major effects on their environment.

One major, well-documented ecosystem alteration by Native Americans peoples was the burning of grasslands and forests, often deliberately, which kept them open and provided habitat for favored food animals such as bison and deer. In the absence of fire, many regions of prairie are invaded by trees and turn into forest. Even more drastic alterations of the landscape occurred when groups of Native Americans settled into permanent communities associated with the development of agriculture or fisheries. Such communities supported large numbers of people who cleared large tracts of land for agriculture. Where early agrarian civilizations developed, such as in the Ohio Valley (Mound Builders) or Central America (Mayan), forests in large regions were cleared or altered. In confined locations, such as the Hawaiian Islands, clearing of forests and hunting by the native peoples drove many species of animals to extinction; in continental areas it is likely that the populations of many species were greatly depleted, but few new extinctions occurred.

When the first Europeans arrived in North America and pushed their settlements into the interior, they were often impressed with the abundance of wildlife (Warren 2003). When Daniel Boone brought colonists over the Cumberland Gap to settle the Ohio Valley, he brought them into a wilderness of large trees, teeming with deer and bear. Two hundred years earlier, however, this same valley had been largely cleared for farms, tended by a dense population of Native Americans. The cause of the disappearance of so many Native Americans was disease. Smallpox, measles, and other diseases carried by the early explorers, from Columbus onward, apparently swept through the continent, decimating Native American populations, which had no resistance to them. Likewise, Cortez’ conquest of Mexico was greatly assisted by the decimation of the Aztec population by a measles epidemic. Thus the first impact of Europeans on wildlife in the Americas was probably to increase wildlife populations through the tremendous and tragic reduction of the populations of indigenous peoples.

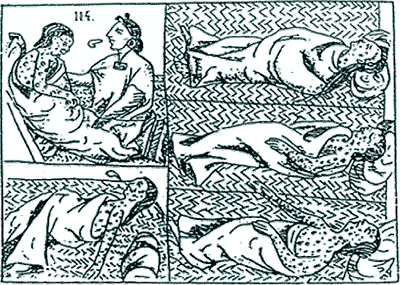

Figure 8.1. Aztec smallpox victims in the sixteenth century. From Historia De Las Cosas de Nueva Espana, Volume 4, Book 12, Lam. cliii, plate 114. Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University.

Disease is more likely to occur in dense populations of animals or humans, because transmission of the disease can occur more easily between individuals and there is a larger supply of susceptible hosts for the disease. Not surprisingly, the high population densities in the late agrarian and early industrial societies of Europe and Asia supported many highly pernicious communicable diseases, such as smallpox, measles, diphtheria, trachoma, whooping cough, chicken pox, bubonic plague (carried by fleas, which were carried by European rats), malaria, typhoid fever, cholera, yellow fever, dengue fever, scarlet fever, amoebic dysentery, influenza, and a number of worm infections (Figure 2.1). Most Europeans were relatively immune to diseases like measles and smallpox because they had been exposed in childhood, and because people from the Old World had experienced selection for more intrinsically defensive immune systems after living for centuries with epidemic diseases (Diamond 1999). When the Europeans came to America they brought these diseases with them. However, Native Americans had absolutely no antibodies to these diseases. To say that the effect of these illnesses on the population of the Americas was devastating would be an understatement. It has been estimated that by the end of the 17th century, between seventy and ninety percent of the population of the Native Americas had died of European-imported diseases.

Era of Abundance (1500-1849)

The richness and abundance of wildlife, especially edible wildlife, during the first 3.5 centuries of colonization and settlement in North America was, from all accounts, awe-inspiring (Warren 2003). Passenger pigeons flew overhead in endless thundering flocks; salmon choked the rivers, to be pitch-forked out as fertilizer; huge herds of bison, antelope, and elk roamed the prairies; whales and seals yielded endless shiploads of oil to burn in lamps. As a result, Americans assumed the supply of such creatures was virtually infinite, a bounty to be harvested at any time for human use. Local depletions of wildlife were noted, but there was always more wildlife over the next range of hills. Some towns and states in this era did try to impose hunting seasons on selected animals to give the game an opportunity to reproduce, but such laws were rarely enforced. More common was the payment of bounties on predators, such as the bounties of one penny each given for wolves by the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630. This was an era of local extinctions where forests were cleared and streams were dammed. While direct negative impacts of westerners on wildlife were relatively small during this era, attitudes that led to the uninhibited destruction of wildlife and wildlife habitat became established. Specifically, the agrarian view that nature needed to be tamed and put to use allowed the widespread destruction of wildlife seen in the next era, and fit in well with the demands of the emerging industrial economy.

While North America was being prepared for explosive environmental change, the roots of Western environmentalism were being quietly established on island colonies around the world (Grove 1992). Islands are miniature, isolated worlds so the effects of environmental degradation, such as the cutting of forests and the extinction of species, were very obvious to the physician-naturalists who joined the colonies. They convinced the governments of the islands to set aside forest reserves as ways of reducing erosion (with such side effects as the filling in of harbors) and of intercepting rain, which provided the water needed for crops. In 1764, the British set up the first forest reserves on Tobago, while in 1769, the French established forest protection laws for Mauritius. The British later applied the lessons learned on the islands to establishing forest protection laws on a much larger scale in India and South Africa (Grove 1992). The end of this era was marked by the publication of Kosmos by the highly regarded German geographer Alexander von Humboldt. This treatise was important because it was ecological in concept, showing how humans were closely connected to the natural world, not apart from it as the dominant western religions generally advocated. In developing his ideas, von Humboldt was one of the first western scientists to draw heavily on the holistic thinking found in Eastern religions such as Hinduism and Buddhism.

Era of Overexploitation (1850-1899)

This era was one in which the North American continent was transformed from a land mass with vast areas unsettled or even unexplored by Europeans to one with cities and farms scattered everywhere and held together by a spidery network of railroads, roads, and telegraph wires. It saw the sudden settlement of the West Coast (catalyzed by the discovery of gold in California), the Civil War, the disappearance of eastern forests, an enormous influx of immigrants from Europe, Asia, and Africa, and the vast expansion of industry and technology. This increase in human population, combined with the technology of the early industrial era and the demands of a market economy, caused wildlife populations to plummet from a combination of unchecked exploitation and environmental alteration. Some examples:

The vast migratory herds of bison on the Great Plains were systematically slaughtered or died of cattle-borne diseases until only a few hundred individuals were left.

The passenger pigeon, whose numbers were once reckoned to be in the billions, became extinct in the wild. Both adults and young were harvested commercially. The last bird died in captivity in 1914.

Heron and egret populations were decimated by hunters shooting them in their breeding colonies for plumes for ladies hats.

The ranges of large predators such as grizzly bears, mountain lions, and wolves became greatly reduced. Mountain lions and wolves were virtually eliminated from eastern North America, as were grizzly bears from California.

White-tailed deer became extremely scarce in the eastern United States through a combination of habitat loss and over-hunting.

Runs of salmon and shad disappeared from many eastern rivers, their runs blocked by mill dams or killed by factory wastes in combination with unlimited fishing.

The drastic decline of wildlife is not really surprising, considering the attitudes of most people living in this era, which were largely characteristic of the combined agrarian and early industrial society of the times. Nature was regarded as something that got in the way of civilization and “progress”, and a source of goods to sell on the market. The agrarian mindset of the time was often frightened by the abundant wild animals and uncontrolled wild ecosystems, and thus thought nature had to be tamed and controlled. Thus popular nature books of the era were filled with drawings of animals doing nasty things to people or to each other: bears clawing hunters, eagles carrying off children, deer goring one another, land crabs attacking goats (Figure 2.2).

Despite this dismal picture, the Era of Overexploitation also contained roots of the modern conservation movement. Over the clamor of self-congratulation for having subdued the “remote, barren, rocky, bushy, wild-woody wilderness” into a “second England,” a few individuals asked if this transformed environment was what people really wanted. Henry David Thoreau in 1855 sat down with his journal beside the local swimming hole in his hometown of Concord, Massachusetts, to consider the ways in which Concord had been altered by two centuries of European settlement and expansion. Following a 1633 account and comparing it to what he saw around him, he concluded that the changes had been drastic. In Walden he listed animals and trees that were no longer present in Concord in 1855, and then wrote:

I take infinite pains to know all the phenomena of spring, for instance thinking that I have here the entire poem, and then, to my chagrin, I hear that it is but an imperfect copy that I possess and have read, that my ancestors have torn out many of the first leaves and grandest passages, and mutilated it in many places. I should not like to think that some demigod had come before me and picked out some of the best stars. I wish to know an entire heaven and an entire earth.

Thoreau was not the first to comment on the changes in the environment he saw around him. Unfortunately, until the twentieth century, writers like Thoreau had little popular audience. The ideology and practice of manifest destiny was quite strong in all parts of the country. People homesteading on the plains, if they read Thoreau at all, would have referred to him as an East Coast dilettante who knew nothing of their struggles to survive in the wilderness.

In 1859, Charles Darwin published The Origin of Species, which further fueled the arguments that humans were part of nature, not separate from it, and that humans had a great impact on the natural world, including the extinction of species. Such ideas did not percolate readily into the consciousness of Americans, but people in this era were becoming dimly aware that America was losing a major part of its heritage. Thus the first game wardens were hired, some states began requiring hunting licenses, fish and game commissions were established to find ways to improve hunting and fishing, and Yellowstone National Park was established. Even these efforts were based on a philosophy that humans could improve upon nature. Thus the new fish and game commissions often took as their major task the introduction of new species to replace native species. The largest railroad cars that existed in this era were those designed to carry fish back and forth across the continent. Striped bass and American shad were introduced to California from the East, with the cars bringing back rainbow trout and Pacific salmon. Carp from Europe were introduced everywhere and were considered to be so much better than native fishes that for a while pools beneath the Washington Monument in Washington D.C. were used to rear them.

Era of Protection (1900-1929)

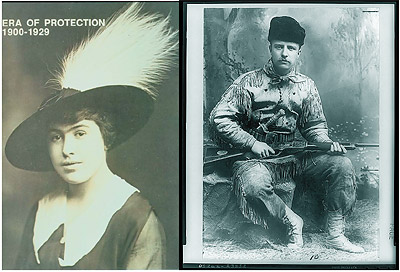

Most Americans in this era were still rather oblivious to the environmental deterioration that was occurring everywhere, but some of them at least were outraged by the uncontrolled hunting that was eliminating populations of the more spectacular animals, from deer to herons. The era began with two significant events: the passage of the Lacey Act in 1900 and the accession of Theodore Roosevelt to the presidency of the United States in 1901 (Figure 2.3). The Lacey Act helped to eliminate market hunting for plumes from birds (by prohibiting interstate commerce in feathers) and was passed in part due to lobbying from newly formed Audubon Societies. The period of the Theodore Roosevelt presidency is considered by many to be a golden age of conservation. Roosevelt, an ardent hunter and conservationist, tripled the size of forest reserves to 148 million acres, and created the U.S. Forest Service to manage and protect them. He also appointed conservationist Gifford Pinchot to head the Forest Service, and pushed Congress into passing legislation that withdrew 80 million acres of public land from exploitation for coal and 4 million acres from exploitation for oil. He created the first national wildlife refuge (which snowballed into the National Wildlife Refuge System), created many national parks and monuments, and beefed up federal enforcement of wildlife laws. Roosevelt also used the 1906 Lacey Act to set aside several million acres of public land as national monuments. In 1913 and 1916 laws were passed that essentially made hunting of most migratory birds, except waterfowl, illegal.

Figure 8.2. Two symbols of the Era of Protection: plumes in ladies hats and Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt is pictured in 1885, age 27. Roosevelt’s experiences as a rancher in North Dakota profoundly shaped his views toward wildlife. Photograph by G.G. Bain, Library of Congress.

The conservation movement in the United States continued to grow in the early part of the twentieth century. Some individuals like John Muir realized that mere preservation of wilderness areas was not enough. He helped found the Sierra Club in 1892 in an attempt to get ordinary people involved in and educated about wilderness. Why, Muir asked in his writings, is there such a dichotomy between lifeless cities and untrammeled wilderness? Can city people care about wilderness they might never see? Muir thought they could. The Sierra Club advocated the establishment of Yosemite National Park in John Muir’s beloved Sierra Nevada Mountains—what he called the “Range of Light.” The Sierra Club attempted to preserve not only the Yosemite Valley itself but also the high country surrounding the valley and the neighboring (and equally beautiful) Hetch Hetchy Valley (Figure 2.3.1). Although Muir and the Sierra Club succeeded in protecting the former, they lost the latter. Hetch Hetchy is now a reservoir owned by the City of San Francisco that supplies power and water to the city.

On the other hand, the basic attitude of resource managers, and the general populace, in this era was still that Nature could be improved upon in order to yield its products to humans in greater abundance. Thus introductions of species continued unabated, and state and federal government initiated major programs in predator control. Predators such as lions, wolves, coyotes, and foxes were considered to be varmints to be shot, poisoned, and trapped in order to increase populations of game animals such as deer and elk and to reduce predation on livestock. In fact, taxpayer-funded predator control programs were still in effect at some state and federal management agencies until the Clinton administration.

Figure 8.3: Hetch Hetchy Valley is a grand landscape garden, one of Nature’s rarest and most precious mountain temples.” – John Muir

The Era of Protection occurred as the US was transitioning from an early to a late industrial society. The increasing consciousness of the value of natural ecosystems and wildlife is a reflection of this, as it the commonly held idea at the time that humans could improve upon nature. However, the science of ecology was still very young then, and as a result the attempts to improve upon nature by resource managers often backfired. The next era is marked by improvement in scientific understanding of wildlife populations and ecosystems and a continuing increase in the valuing of wildlife.

Era of Game Management (1930-1965)

This era began in 1930 when the Report of the Committee on North American Game Policy was issued. The committee, chaired by Aldo Leopold, made strong recommendations for better research and management of game animals. Leopold was the founder of the University of Wisconsin’s Department of Wildlife Management, and in 1933, Leopold published his book Game Management, which is often used as the milestone heralding the birth of wildlife biology as a profession. Throughout this era there was a gradually growing awareness that creatures other than game animals also needed protection. National Parks became more restrictive in how they could be used, and the Wilderness Act of 1964 allowed the creation of wilderness areas on U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management lands. The growing awareness found its philosophical justification in Leopold’s Sand County Almanac (1949), which in elegant prose outlined the need for environmental ethics and the maintenance of intact ecosystems.

The focus in this era was on improving wildlife and fish populations to satisfy the increasing demand for recreational hunting and fishing. State and federal agencies dealing with wildlife and fisheries were strengthened and new sources of funding such as duck stamps were found. Excise taxes on guns and ammunition (Pittman-Robertson Act of 1937) and on fishing tackle and boats (Dingell-Johnson Act of 1950) provided reliable sources of funds for research and management of wildlife and fisheries, respectively. Although there was a great deal of money spent on habitat management and restoration, such as the acquisition of wetlands for waterfowl refuges, a prevailing point of view was that much of the recreational demand could be satisfied by raising fish and game under artificial conditions. The animals so produced were then released into areas where hunting and fishing pressure was intense. Thus many states financed large game farms to produce pheasants, ducks, and quail for hunters. Even more extensive were the fish hatcheries, especially for producing trout and salmon. These were often created in exchange for fisheries lost when dams cut off access to upstream spawning areas or flooded streams. It was optimistically assumed that humans could produce more and better fish in hatcheries than natural environments could produce.

In 1935, Aldo Leopold and Bob Marshall worked together to found the Wilderness Society. The Society was founded as an activist group that was committed to education and to action and advocating in favor of wilderness. Bob Marshall committed his own money and hours of his time to assess the environmental problems caused by the road-building projects of the New Deal. As a result of the Society’s work, legislation was passed in the 1960s and 1970s designating roadless areas and wilderness areas separate from national parks. The Society, along with many other conservation groups, was also involved in lobbying for passage of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act and the Endangered Species Act.

Aldo Leopold was the philosophical leader of the Wilderness Society. He declared that the Society would promote a new attitude, “an intelligent humility toward man’s place in nature.” His Essay from Round River articulated for the first time the idea that all parts of an ecosystem play important roles, and that no organism should be removed from an ecosystem. “The first rule of tinkering,” he wrote, “is to keep all the parts.” In his classic Sand County Almanac, Leopold wrote “there are those who can live without wild things and those who cannot… These essays are the delights and the dilemmas of one who cannot.” He describes a land ethic, drawing upon the ideas of Thoreau and others: “Perhaps a shift in values can be achieved by reappraising things unnatural, tame, and confined in terms of things natural, wild, and free.” Leopold, who grew up as a hunter, saw that shift happen in his own thinking. He described a dying wolf losing the “green fire” from its eyes and later comments, “To be trained as an ecologist is to live alone in a world of wounds.”

Between 1940 and 1960, there were very few new developments in conservation. In 1946, the Bureau of Land Management was formed to administer federal grazing lands and federal lands that had potential for mineral and oil exploration. However, there was much controversy around public lands. The opposition to conservation was led by the timber industry in the Northwest and cattle ranchers in the West. This is typical of an early industrial view of ecosystems as a collection of commodities. Aldo Leopold’s “land ethic” was not only in direct conflict with this earlier mode of thinking, it was also in conflict with the descendants of those early settlers—those who wished to exploit public lands for the commodities (oil, minerals, pasture, timber) they represented. As we shall see, precisely the same conflict is going on today.

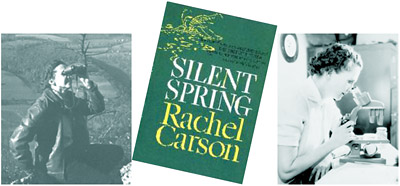

In 1962, Rachel Carson, a biologist, published Silent Spring (Figure 2.4). This book jolted the public into seeing that the benefits being brought by pesticides and other chemicals were having terrible side effects, most prominently the loss of many species of birds and mammals. The title echoed Aldo Leopold’s worried question from Sand County Almanac as he watched the decreasing numbers of wild birds, “What if there was no more goose music?” Carson documented the use of pesticides and other chemicals and the pollution of air and water. She showed that the pesticide DDT could not only kill birds but also concentrate in the food chain. “If we keep using pesticides, and if we keep polluting our world,” Carson asked, “will we finish the job the first European settlers began? Some day will there be no more birds singing in the spring?” Her words and Leopold’s were prophetic. Research on this question has shown that not only are we exterminating wildlife, but we are also turning the oceans into toxic dumps and may be endangering our own lives by dumping toxic chemicals into the air and into the upper atmosphere. Today, over 35 years after Rachel Carson wrote her book, her “silent spring” may still come to pass. Migratory bird populations, though largely protected from the most egregious pesticides in the United States, are killed by those same pesticides in Central and South America. Their winter habitats are also being destroyed. Meanwhile, back in the developed world, subtle new pesticides, with subtle new effects are being used.

Figure 8.4. Rachel Carson was a scientist and writer employed by the US Fish and Wildlife Service. Silent Spring was a milestone in environmental protection which took enormous courage to write and publish. Photos by USFWS.

Era of Environmental Management (1966-1979)

This brief era was a transitional one in which the public, biologists, and other scientists started clamoring for more environmental protection and the politicians reluctantly began to acquiesce to the demands. It began in 1966 because the first (but toothless) federal Endangered Species Act was passed then; this act was strengthened in 1969 and again in 1973, but weakened in 1978. This was the period in which the National Environmental Quality Act (NEQA) was passed (in 1969), requiring environmental impact statements for new projects. In 1970, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was established. Public sentiment was expressed in the extraordinary outpouring of concern seen on Earth Day 1972. Environmental groups grew rapidly. Enrollments in environmental programs at universities skyrocketed and states began to pass laws similar to the federal NEQA legislation. Even California, with conservative Ronald Reagan as governor, passed a strong California Environmental Policy Act and an endangered species act similar to the federal act.

The prevailing feeling in this era seemed to be that there was nothing fundamentally wrong with the environment. Environmental problems could be solved with proper management that balanced ecological and economic interests. A few natural areas could be set aside, for example, to protect species such as kit foxes or kangaroo rats, that were being eliminated by development. The effects of water pollution could be taken care of by reducing discharges or using pesticides that degraded more quickly. The increasingly polluted air of the cities could be cleaned up by people driving slightly smaller cars and by building power plants out in the desert.

Between 1965 and 1980, over two dozen pieces of legislation were passed on the federal level and many times that number on state and local levels to protect wildlife and wildlife habitat. This legislation included the Safe Drinking Water Act, the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act, the Toxic Substances Control Act, and others that seek to decrease pollution. Other legislation such as the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act and the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act attempted to regulate land use and to set aside pieces of land that are free from development. Wildlife conservation was addressed in the federal Endangered Species Act as well as in similar legislation on the state level. All of this legislation was a direct result of the education and activism in local communities that began to take place in the early 1960s, in large part from the stimulus of Rachel Carson’s book. This was also the era, however, when the United States defoliated huge areas of forest in Vietnam with Agent Orange as part of its military strategy.

Era of Conservation Biology (1980-??)

The present era is considered to have begun in 1980 because that was when the book Conservation Biology: an Evolutionary-Ecological Perspective, edited by Michael Soulé and Bruce Wilcox, came out. This book gave a major push to the development of Conservation Biology as a distinct field, a science devoted to finding ways to preserve the diversity of life on Earth. The year 1980 also marked the Alaska National Interest Lands Act, which set aside (more or less) 101 million acres of Alaska as National Park, National Monument, or National Wildlife Refuge. This was done in recognition that the wilds of Alaska, one of the most pristine areas of the world, were on the verge of being spoiled by mining, settlement, and overexploitation of wildlife. In contrast, 1980 was also the year Ronald Reagan was elected President of the United States with a profoundly anti-environmental philosophy. The initial years of this era, therefore, were ones of weakened environmental agencies, confrontational politics on environmental issues, and avoidance of developing serious solutions to major problems such as acid rain.

Despite the attempts to undermine progress made in solving environmental problems, major progress has been made. Scientists and, increasingly, the public are realizing that we are in an environmental crisis of global proportions. Human populations are still climbing at an exponential rate, the atmosphere is warming, both tropical and temperate rainforests are being cut at alarming rates, and serious pollution is much more prevalent than admitted previously. From the perspective of wildlife this means species are being lost almost on a daily basis. Recognition of these problems, however, means that we can find solutions to them. The essays that follow discuss many of these problems and their origins as well as solutions. We have labeled the present era the “Era of Conservation Biology” on the optimistic assumption that our increased awareness of the environmental problems of the world coupled with our increased knowledge of ecology will allow us to solve those problems. The question for you is: can the major changes in public attitudes needed to change our present direction in global use and abuse happen? Is this even desirable? Do the words of Henry Beston, written in 1928, still resonate or do they represent an old-fashioned attitude, irrelevant in the modern world:

We need another and a wiser and perhaps a more mystical concept of animals. Remote from universal nature, and living by complicated artifice, man in civilization surveys the creature through the glass of his knowledge and sees thereby a feather magnified and the whole image in distortion. We patronize them for their incompleteness, for their tragic fate of having taken form so far below ourselves. And therein we err, and greatly err. For the animal shall not be measured by man. In a world older and more complete than ours they move finished and complete, gifted with extensions of the senses we have lost or never attained, living by voices we shall never hear. They are not brethren, they are not underlings; they are other nations, caught with ourselves in the net of life and time, fellow prisoners of the splendor and travail of the earth.

It may be that future generations will label our era the Era of Extinction.

Contributors and Attributions

Modified from the following sources:

The MarineBio Conservation Society. (n.d.) Essays On Wildlife Conservation ~ MarineBio Conservation Society. Edited by Peter Moyle, et al. The MarineBio Conservation Society. Retrieved September 4, 2025, Chapter 2: A history of wildlife in North America, openly shared for revision as noted: https://www.marinebio.org/creatures/essays-on-wildlife-conservation/

Additional references and citations from the above sources can be found in References in the backmatter.

8. A History of Wildlife in North America shared under a CC BY-NC-SA license