3 Evolution and Adaptation

All species of living organisms, from bacteria to baboons to blueberries, evolved at some point from a different species. Although it may seem that living things today stay much the same, that is not the case—evolution is an ongoing process.

Figure 3.1: All organisms are products of evolution adapted to their environment. (a) Saguaro (Carnegiea gigantea) can soak up 750 liters of water in a single rain storm, enabling these cacti to survive the dry conditions of the Sonora desert in Mexico and the Southwestern United States. (b) The Andean semiaquatic lizard (Potamites montanicola) discovered in Peru in 2010 lives between 1,570 to 2,100 meters in elevation, and, unlike most lizards, is nocturnal and swims. Scientists still do not know how these ectotherms (cold-blooded animals) are able to move in the cold (10 to 15°C) temperatures of the Andean night (credit a: modification of work by Gentry George, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; credit b: modification of work by Germán Chávez and Diego Vásquez, ZooKeys).

The theory of evolution is the unifying theory of biology, meaning it is the framework within which biologists ask questions about the living world. Its power is that it provides direction for predictions about living things that are borne out in experiment after experiment. The Ukrainian-born American geneticist Theodosius Dobzhansky famously wrote that “nothing makes sense in biology except in the light of evolution,” (Dobshansky, 1964). He meant that the tenet that all life has evolved and diversified from a common ancestor is the foundation from which we approach all questions in biology.

Charles Darwin and Natural Selection

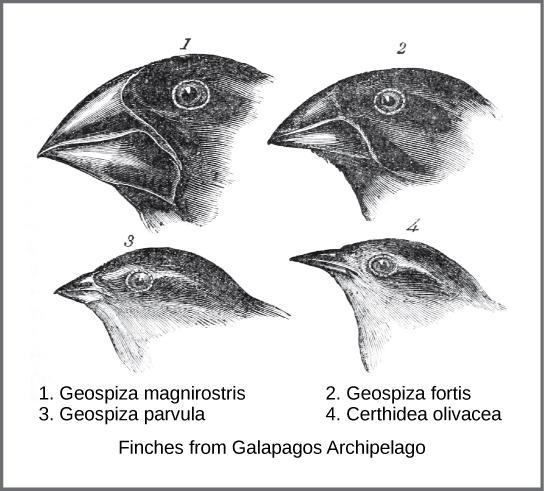

In the mid-nineteenth century, the actual mechanism for evolution was independently conceived of and described by two naturalists: Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace. Importantly, each naturalist spent time exploring the natural world on expeditions to the tropics. From 1831 to 1836, Darwin traveled around the world on H.M.S. Beagle, including stops in South America, Australia, and the southern tip of Africa. Wallace traveled to Brazil to collect insects in the Amazon rainforest from 1848 to 1852 and to the Malay Archipelago from 1854 to 1862. Darwin’s journey, like Wallace’s later journeys to the Malay Archipelago, included stops at several island chains, the last being the Galápagos Islands west of Ecuador. On these islands, Darwin observed species of organisms on different islands that were clearly similar, yet had distinct differences. For example, the ground finches inhabiting the Galápagos Islands comprised several species with a unique beak shape (Figure 3.2). The species on the islands had a graded series of beak sizes and shapes with very small differences between the most similar. He observed that these finches closely resembled another finch species on the mainland of South America. Darwin imagined that the island species might be species modified from one of the original mainland species. Upon further study, he realized that the varied beaks of each finch helped the birds acquire a specific type of food. For example, seed-eating finches had stronger, thicker beaks for breaking seeds, and insect-eating finches had spear-like beaks for stabbing their prey.

Figure 3.2: Darwin observed that beak shape varies among finch species. He postulated that the beak of an ancestral species had adapted over time to equip the finches to acquire different food sources. Image is available on the public domain.

Wallace and Darwin both observed similar patterns in other organisms and they independently developed the same explanation for how and why such changes could take place. Darwin called this mechanism natural selection. Natural selection, also known as “survival of the fittest,” is the more prolific reproduction of individuals with favorable traits that survive environmental change because of those traits; this leads to evolutionary change.

For example, a population of giant tortoises found in the Galapagos Archipelago was observed by Darwin to have longer necks than those that lived on other islands with dry lowlands. These tortoises were “selected” because they could reach more leaves and access more food than those with short necks. In times of drought when fewer leaves would be available, those that could reach more leaves had a better chance to eat and survive than those that couldn’t reach the food source. Consequently, long-necked tortoises would be more likely to be reproductively successful and pass the long-necked trait to their offspring. Over time, only long-necked tortoises would be present in the population.

Natural selection, Darwin argued, was an inevitable outcome of three principles that operated in nature. First, most characteristics of organisms are inherited, or passed from parent to offspring. Although no one, including Darwin and Wallace, knew how this happened at the time, it was a common understanding. Second, more offspring are produced than are able to survive, so resources for survival and reproduction are limited. The capacity for reproduction in all organisms outstrips the availability of resources to support their numbers. Thus, there is competition for those resources in each generation. Both Darwin and Wallace’s understanding of this principle came from reading an essay by the economist Thomas Malthus who discussed this principle in relation to human populations. Third, offspring vary among each other in regard to their characteristics and those variations are inherited. Darwin and Wallace reasoned that offspring with inherited characteristics which allow them to best compete for limited resources will survive and have more offspring than those individuals with variations that are less able to compete. Because characteristics are inherited, these traits will be better represented in the next generation. This will lead to change in populations over generations in a process that Darwin called descent with modification. Ultimately, natural selection leads to greater adaptation of the population to its local environment; it is the only mechanism known for adaptive evolution.

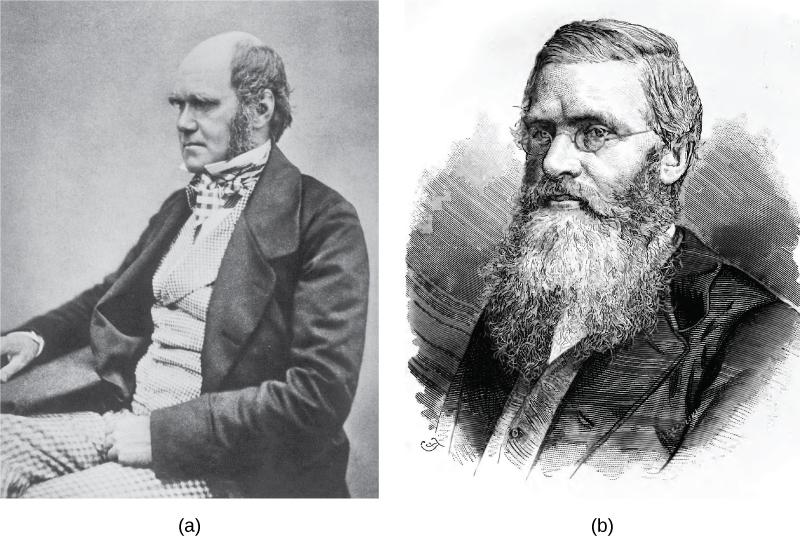

Papers by Darwin and Wallace (Figure 3.3) presenting the idea of natural selection were read together in 1858 before the Linnean Society in London. The following year Darwin’s book, On the Origin of Species, was published. His book outlined in considerable detail his arguments for evolution by natural selection.

Figure 3.3: Both (a) Charles Darwin and (b) Alfred Wallace wrote scientific papers on natural selection that were presented together before the Linnean Society in 1858.

Processes and Patterns of Evolution

Natural selection can only take place if there is variation, or differences, among individuals in a population. Importantly, these differences must have some genetic basis; otherwise, the selection will not lead to change in the next generation. This is critical because variation among individuals can be caused by non-genetic reasons such as an individual being taller because of better nutrition rather than different genes.

Genetic diversity in a population comes from two main mechanisms: mutation and sexual reproduction. Mutation, a change in DNA, is the ultimate source of new alleles, or new genetic variation in any population. The genetic changes caused by mutation can have one of three outcomes on the phenotype. A mutation affects the phenotype of the organism in a way that gives it reduced fitness—lower likelihood of survival or fewer offspring. A mutation may produce a phenotype with a beneficial effect on fitness. And, many mutations will also have no effect on the fitness of the phenotype; these are called neutral mutations. Mutations may also have a whole range of effect sizes on the fitness of the organism that expresses them in their phenotype, from a small effect to a great effect. Mutations can occur during both asexual and sexual reproduction.

Sexual reproduction also leads to genetic diversity: when two parents reproduce, unique combinations of alleles assemble to produce the unique genotypes and thus phenotypes in each of the offspring. Sexual reproduction does not create new alleles, but new combinations of alleles which means more genetic diversity in the population.

A heritable trait that helps the survival and reproduction of an organism in its present environment is called an adaptation. Scientists describe groups of organisms becoming adapted to their environment when a change in the range of genetic variation occurs over time that increases or maintains the “fit” of the population to its environment. The webbed feet of platypuses are an adaptation for swimming. The snow leopards’ thick fur is an adaptation for living in the cold. The cheetahs’ fast speed is an adaptation for catching prey.

Whether or not a trait is favorable depends on the environmental conditions at the time. The same traits are not always selected because environmental conditions can change. For example, consider a species of plant that grew in a moist climate and did not need to conserve water. Large leaves were selected because they allowed the plant to obtain more energy from the sun. Large leaves require more water to maintain than small leaves, and the moist environment provided favorable conditions to support large leaves. After thousands of years, the climate changed, and the area no longer had excess water. The direction of natural selection shifted so that plants with small leaves were selected because those populations were able to conserve water to survive the new environmental conditions.

The evolution of species has resulted in enormous variation in form and function. Sometimes, evolution gives rise to groups of organisms that become tremendously different from each other. When two species evolve in diverse directions from a common point, it is called divergent evolution. Such divergent evolution can be seen in the forms of the reproductive organs of flowering plants which share the same basic anatomies; however, they can look very different as a result of selection in different physical environments and adaptation to different kinds of pollinators (Figure 3.4).

Figure 3.4: Flowering plants evolved from a common ancestor. Notice that the (a) dense blazing star (Liatrus spicata) and the (b) purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea) vary in appearance, yet both share a similar basic morphology (credit a: modification of work by Drew Avery; credit b: modification of work by Cory Zanker).

In other cases, similar phenotypes evolve independently in distantly related species. For example, flight has evolved in both bats and insects, and they both have structures we refer to as wings, which are adaptations to flight. However, the wings of bats and insects have evolved from very different original structures. This phenomenon is called convergent evolution, where similar traits evolve independently in species that do not share a recent common ancestry. The two species came to the same function, flying, but did so separately from each other.

These physical changes occur over enormous spans of time and help explain how evolution occurs. Natural selection acts on individual organisms, which in turn can shape an entire species. Although natural selection may work in a single generation on an individual, it can take thousands or even millions of years for the genotype of an entire species to evolve. It is over these large time spans that life on earth has changed and continues to change.

Formation of New Species

Although all life on earth shares various genetic similarities, only certain organisms combine genetic information by sexual reproduction and have offspring that can then successfully reproduce. Scientists call such organisms members of the same biological species.

Species and the Ability to Reproduce

A species is a group of individual organisms that interbreed and produce fertile, viable offspring. According to this definition, one species is distinguished from another when, in nature, it is not possible for matings between individuals from each species to produce fertile offspring.

Members of the same species share both external and internal characteristics, which develop from their DNA. The closer relationship two organisms share, the more DNA they have in common, just like people and their families. People’s DNA is likely to be more like their father or mother’s DNA than their cousin or grandparent’s DNA. Organisms of the same species have the highest level of DNA alignment and therefore share characteristics and behaviors that lead to successful reproduction.

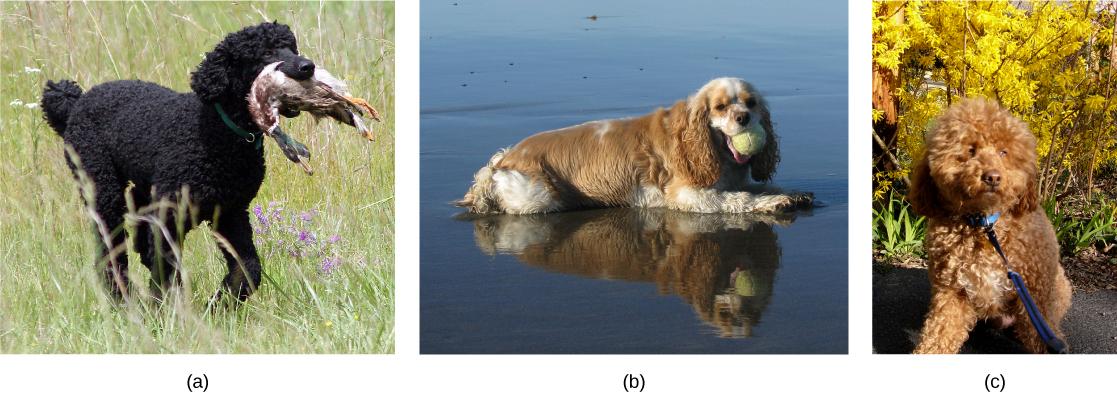

Species’ appearance can be misleading in suggesting an ability or inability to mate. For example, even though domestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) display phenotypic differences, such as size, build, and coat, most dogs can interbreed and produce viable puppies that can mature and sexually reproduce (Figure 3.5).

Figure 3.5: The (a) poodle and (b) cocker spaniel can reproduce to produce a breed known as (c) the cockapoo (credit a: modification of work by Sally Eller, Tom Reese; credit b: modification of work by Jeremy McWilliams; credit c: modification of work by Kathleen Conklin).

Figure 3.5: The (a) poodle and (b) cocker spaniel can reproduce to produce a breed known as (c) the cockapoo (credit a: modification of work by Sally Eller, Tom Reese; credit b: modification of work by Jeremy McWilliams; credit c: modification of work by Kathleen Conklin).

In other cases, individuals may appear similar although they are not members of the same species. For example, even though bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) and African fish eagles (Haliaeetus vocifer) are both birds and eagles, each belongs to a separate species group (Figure 3.6). If humans were to artificially intervene and fertilize the egg of a bald eagle with the sperm of an African fish eagle and a chick did hatch, that offspring, called a hybrid (a cross between two species), would probably be infertile—unable to successfully reproduce after it reached maturity. Different species may have different genes that are active in development; therefore, it may not be possible to develop a viable offspring with two different sets of directions. Thus, even though hybridization may take place, the two species still remain separate.

Figure 3.6: The (a) African fish eagle is similar in appearance to the (b) bald eagle, but the two birds are members of different species (credit a: modification of work by Nigel Wedge; credit b: modification of work by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service).

Figure 3.6: The (a) African fish eagle is similar in appearance to the (b) bald eagle, but the two birds are members of different species (credit a: modification of work by Nigel Wedge; credit b: modification of work by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service).

Populations of species share a gene pool: a collection of all the variants of genes in the species. Again, the basis to any changes in a group or population of organisms must be genetic for this is the only way to share and pass on traits. When variations occur within a species, they can only be passed to the next generation along two main pathways: asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction. The change will be passed on asexually simply if the reproducing cell possesses the changed trait. For the changed trait to be passed on by sexual reproduction, a gamete, such as a sperm or egg cell, must possess the changed trait. In other words, sexually-reproducing organisms can experience several genetic changes in their body cells, but if these changes do not occur in a sperm or egg cell, the changed trait will never reach the next generation. Only heritable traits can evolve. Therefore, reproduction plays a paramount role for genetic change to take root in a population or species. In short, organisms must be able to reproduce with each other to pass new traits to offspring.

Speciation

The biological definition of species, which works for sexually reproducing organisms, is a group of actually or potentially interbreeding individuals. There are exceptions to this rule. Many species are similar enough that hybrid offspring are possible and may often occur in nature, but for the majority of species this rule generally holds. In fact, the presence in nature of hybrids between similar species suggests that they may have descended from a single interbreeding species, and the speciation process may not yet be completed.

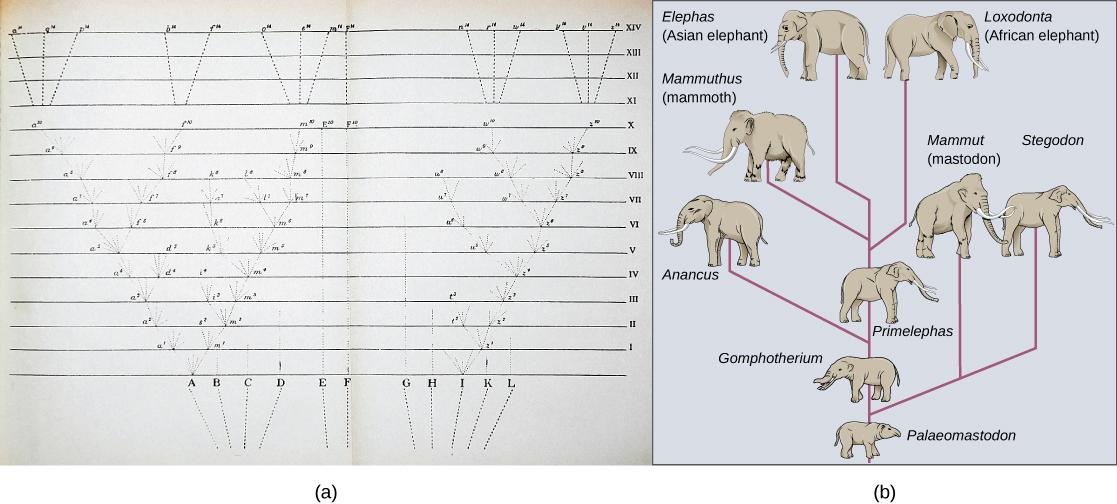

Given the extraordinary diversity of life on the planet there must be mechanisms for speciation: the formation of two species from one original species. Darwin envisioned this process as a branching event and diagrammed the process in the only illustration found in On the Origin of Species (Figure 3.7 a). Compare this illustration to the diagram of elephant evolution (Figure 3.7 b), which shows that as one species changes over time, it branches to form more than one new species, repeatedly, as long as the population survives or until the organism becomes extinct.

Figure 3.7: The only illustration in Darwin’s On the Origin of Species is (a) a diagram showing speciation events leading to biological diversity. The diagram shows similarities to phylogenetic charts that are drawn today to illustrate the relationships of species. (b) Modern elephants evolved from the Palaeomastodon, a species that lived in Egypt 35–50 million years ago.

Figure 3.7: The only illustration in Darwin’s On the Origin of Species is (a) a diagram showing speciation events leading to biological diversity. The diagram shows similarities to phylogenetic charts that are drawn today to illustrate the relationships of species. (b) Modern elephants evolved from the Palaeomastodon, a species that lived in Egypt 35–50 million years ago.

For speciation to occur, two new populations must be formed from one original population and they must evolve in such a way that it becomes impossible for individuals from the two new populations to interbreed. Biologists have proposed mechanisms by which this could occur that fall into two broad categories. Allopatric speciation (allo- = “other”; -patric = “homeland”) involves geographic separation of populations from a parent species and subsequent evolution. Sympatric speciation (sym- = “same”; -patric = “homeland”) involves speciation occurring within a parent species remaining in one location.

Biologists think of speciation events as the splitting of one ancestral species into two descendant species. There is no reason why there might not be more than two species formed at one time except that it is less likely and multiple events can be conceptualized as single splits occurring close in time.

Allopatric Speciation

A geographically continuous population has a gene pool that is relatively homogeneous. Gene flow, the movement of alleles across the range of the species, is relatively free because individuals can move and then mate with individuals in their new location. Thus, the frequency of an allele at one end of a distribution will be similar to the frequency of the allele at the other end. When populations become geographically discontinuous, that free-flow of alleles is prevented. When that separation lasts for a period of time, the two populations are able to evolve along different trajectories. Thus, their allele frequencies at numerous genetic loci gradually become more and more different as new alleles independently arise by mutation in each population. Typically, environmental conditions, such as climate, resources, predators, and competitors for the two populations will differ causing natural selection to favor divergent adaptations in each group.

Isolation of populations leading to allopatric speciation can occur in a variety of ways: a river forming a new branch, erosion forming a new valley, a group of organisms traveling to a new location without the ability to return, or seeds floating over the ocean to an island. The nature of the geographic separation necessary to isolate populations depends entirely on the biology of the organism and its potential for dispersal. If two flying insect populations took up residence in separate nearby valleys, chances are, individuals from each population would fly back and forth continuing gene flow. However, if two rodent populations became divided by the formation of a new lake, continued gene flow would be unlikely; therefore, speciation would be more likely.

Biologists group allopatric processes into two categories: dispersal and vicariance. Dispersal is when a few members of a species move to a new geographical area, and vicariance is when a natural situation arises to physically divide organisms.

Scientists have documented numerous cases of allopatric speciation taking place. For example, along the west coast of the United States, two separate sub-species of spotted owls exist. The northern spotted owl has genetic and phenotypic differences from its close relative: the Mexican spotted owl, which lives in the south (Figure 3.8).

Figure 3.8: The northern spotted owl and the Mexican spotted owl inhabit geographically separate locations with different climates and ecosystems. The owl is an example of allopatric speciation (credit “northern spotted owl”: modification of work by John and Karen Hollingsworth; credit “Mexican spotted owl”: modification of work by Bill Radke).

Additionally, scientists have found that the further the distance between two groups that once were the same species, the more likely it is that speciation will occur. This seems logical because as the distance increases, the various environmental factors would likely have less in common than locations in close proximity. Consider the two owls: in the north, the climate is cooler than in the south; the types of organisms in each ecosystem differ, as do their behaviors and habits; also, the hunting habits and prey choices of the southern owls vary from the northern owls. These variances can lead to evolved differences in the owls, and speciation likely will occur.

Adaptive Radiation

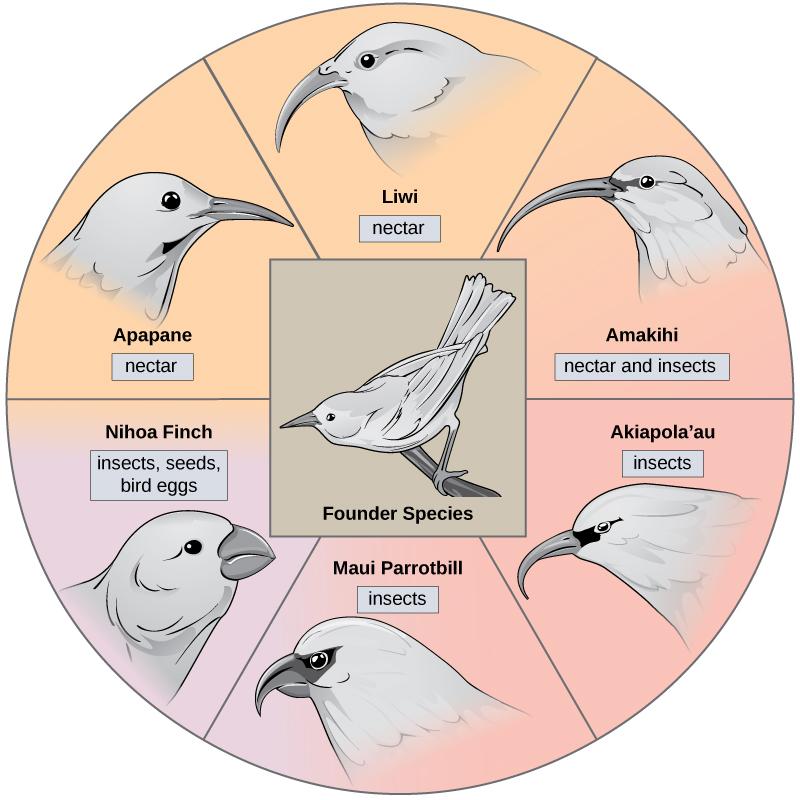

In some cases, a population of one species disperses throughout an area, and each finds a distinct niche or isolated habitat. Over time, the varied demands of their new lifestyles lead to multiple speciation events originating from a single species. This is called adaptive radiation because many adaptations evolve from a single point of origin; thus, causing the species to radiate into several new ones. Island archipelagos like the Hawaiian Islands provide an ideal context for adaptive radiation events because water surrounds each island which leads to geographical isolation for many organisms. The Hawaiian honeycreeper illustrates one example of adaptive radiation. From a single species, called the founder species, numerous species have evolved, including the six shown in Figure 3.9. Figure 3.9: The honeycreeper birds illustrate adaptive radiation. From one original species of bird, multiple others evolved, each with its own distinctive characteristics.

Figure 3.9: The honeycreeper birds illustrate adaptive radiation. From one original species of bird, multiple others evolved, each with its own distinctive characteristics.

Notice the differences in the species’ beaks in Figure 3.9. Evolution in response to natural selection based on specific food sources in each new habitat led to evolution of a different beak suited to the specific food source. The seed-eating bird has a thicker, stronger beak which is suited to break hard nuts. The nectar-eating birds have long beaks to dip into flowers to reach the nectar. The insect-eating birds have beaks like swords, appropriate for stabbing and impaling insects. Darwin’s finches are another example of adaptive radiation in an archipelago.

Sympatric Speciation

Can divergence occur if no physical barriers are in place to separate individuals who continue to live and reproduce in the same habitat? The answer is yes. The process of speciation within the same space is called sympatric speciation; the prefix “sym” means same, so “sympatric” means “same homeland” in contrast to “allopatric” meaning “other homeland.” A number of mechanisms for sympatric speciation have been proposed and studied.

Reproductive Isolation

Given enough time, the genetic and phenotypic divergence between populations will affect characters that influence reproduction: if individuals of the two populations were to be brought together, mating would be less likely, but if mating occurred, offspring would be non-viable or infertile. Many types of diverging characters may affect the reproductive isolation, the ability to interbreed, of the two populations.

For example, many organisms only reproduce at certain times of the year, often just annually. Differences in breeding schedules, called temporal isolation, can act as a form of reproductive isolation. For example, two species of frogs inhabit the same area, but one reproduces from January to March, whereas the other reproduces from March to May (Figure 3.10).

Figure 3.10: These two related frog species exhibit temporal reproductive isolation. (a) Rana aurora breeds earlier in the year than (b) Rana boylii (credit a: modification of work by Mark R. Jennings, USFWS; credit b: modification of work by Alessandro Catenazzi).

Figure 3.10: These two related frog species exhibit temporal reproductive isolation. (a) Rana aurora breeds earlier in the year than (b) Rana boylii (credit a: modification of work by Mark R. Jennings, USFWS; credit b: modification of work by Alessandro Catenazzi).

Behavioral isolation occurs when the presence or absence of a specific behavior prevents reproduction from taking place. For example, male fireflies use specific light patterns to attract females. Various species of fireflies display their lights differently. If a male of one species tried to attract the female of another, she would not recognize the light pattern and would not mate with the male.

Habitat Influence on Speciation

Sympatric speciation may also take place in ways other than polyploidy. For example, consider a species of fish that lives in a lake. As the population grows, competition for food also grows. Under pressure to find food, suppose that a group of these fish had the genetic flexibility to discover and feed off another resource that was unused by the other fish. What if this new food source was found at a different depth of the lake? Over time, those feeding on the second food source would interact more with each other than the other fish; therefore, they would breed together as well. Offspring of these fish would likely behave as their parents: feeding and living in the same area and keeping separate from the original population. If this group of fish continued to remain separate from the first population, eventually sympatric speciation might occur as more genetic differences accumulated between them.

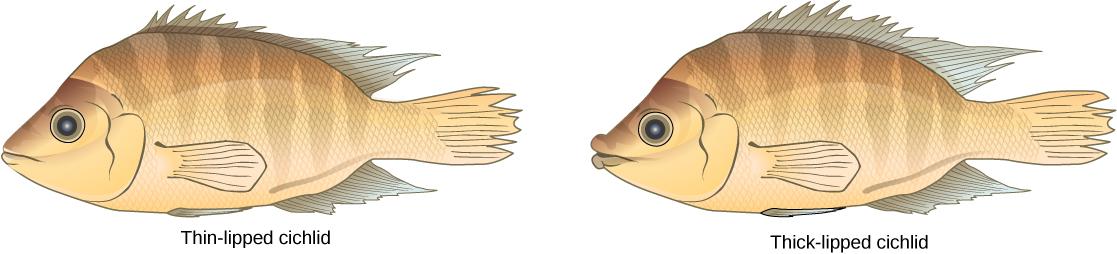

This scenario does play out in nature, as do others that lead to reproductive isolation. One such place is Lake Victoria in Africa, famous for its sympatric speciation of cichlid fish. Researchers have found hundreds of sympatric speciation events in these fish, which have not only happened in great number, but also over a short period of time. Figure 3.11 shows this type of speciation among a cichlid fish population in Nicaragua. In this locale, two types of cichlids live in the same geographic location but have come to have different morphologies that allow them to eat various food sources.

Figure 3.11: Cichlid fish from Lake Apoyeque, Nicaragua, show evidence of sympatric speciation. Lake Apoyeque, a crater lake, is 1800 years old, but genetic evidence indicates that the lake was populated only 100 years ago by a single population of cichlid fish. Nevertheless, two populations with distinct morphologies and diets now exist in the lake, and scientists believe these populations may be in an early stage of speciation.

Figure 3.11: Cichlid fish from Lake Apoyeque, Nicaragua, show evidence of sympatric speciation. Lake Apoyeque, a crater lake, is 1800 years old, but genetic evidence indicates that the lake was populated only 100 years ago by a single population of cichlid fish. Nevertheless, two populations with distinct morphologies and diets now exist in the lake, and scientists believe these populations may be in an early stage of speciation.

Contributors and Attributions

Modified from the following sources:

Ecology for All! By LibreTexts, Chapter 3.1 and Chapter 3.2 licensed CC BY-NC-SA

Additional references and citations from the above sources can be found in References in the backmatter.

3. Evolution and Adaptation is shared under a CC BY-NC-SA license